Chapter One Introduction

1.1 Research Background

Numerous studies have been made on the identity of females, whether it’s the identity of modern urban office ladies or rural migrant female workers. Scholars seem to have reached all the social groups but one specific group of young women hasn’t been given adequate attention, namely, school girls in universities. This group of young women exist socially in the institutional context of tertiary education, and they will make up a considerable proportion in the nation’s workforce, so they deserve some academic attention as any other sub-group of females.

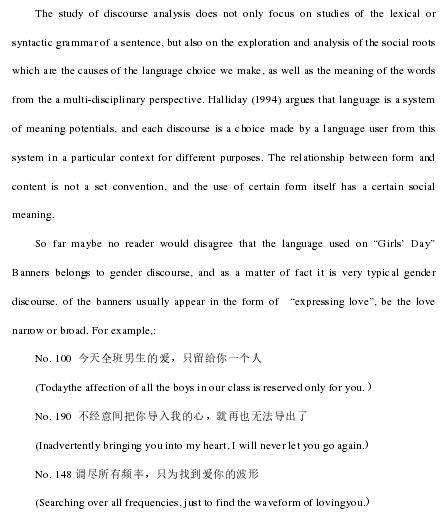

“女生节”, “Female Students’ Day”, or “Girls’ Day”, is a festival which has emerged in recent years. This special festival has been a popular trend and it seems that it is being celebrated by more and more students and universities. “Girls’ Day” is set on March 7th, and around this time of the year, one major way for students to celebrate this festival is putting up banners on campus, on which various messages are sent, mostly by male students toward female students, as a way of paying compliments or sending good wishes.

In the institutional setting of universities, some students would accept the slogans on the banners without any questioning. But in one report the author found online1, on the one hand a female student they interviewed said “the most elegant and meaningful banners are the ones from Department of Economics (经院的条幅写的最高雅最有意义了)”; on the other hand the report showed examples of the banners like ‘we already get tired of IS or LM curves, what we won’t get tired of, is your S curves’ (早就看厌了 IS、LM 曲线,看不厌的还是你们的 S 曲线), which clearly implies a sexual undertone but this female student didn’t even realize it or comment on it. This proves the cold fact that women are being discursively constructed in a misleading way. Also according to another report2, multiple complaints have been filed from some students who already noticed the bias in banners which are essentially ‘public harassment’. This thesis intends to reveal more to the public and raise the awareness of the public.

..........................

1.2 Research Significance

In order to avoid similar sexual harassment or content that is detrimental to the female image, and to carry out the Girls' Day activities better. Both the producer of the Girls’ Day banners, the interpreters and the general public as well, needs to be aware of this. Female students need to improve their awareness of discrimination, not only on campus, but also in other aspects of social life. They need to take the initiative to say no to defend their identity; for the producers of the banners, be them men or women, it is necessary to watch out the language they use while celebrating such a festival under the premise of mutual respect; in addition to the content of the rough language that has emerged, it is necessary for university administrators to strengthen supervision and realize the role such as banners of Girls’ Day play in establishing and maintaining the relationship between men and women.

..........................

Chapter Two Literature Review

2.1 Gender Studies

The study of language and gender started early, rising from scholars in nearly all fields whether it is sociology, anthropology, or linguistics, and the year 1975 was key in launching the field of them combined. That year saw the publication of three books that proved pivotal: Like Robin Lakoff’s Language and Woman’s Place (the first part of which had appeared in Language and Society two years earlier [1973]), which focuses on a deficit approach of studying the relationship between gender and language, she tried to figure out the linguistic evidences for women’s powerlessness and subordinate status as compared to men. All the pioneering works emerged with the identification of male norms as human norms, and the biological determination of women’s and men’s behavior (Kendall & Tannen, 2015).

The early focus is on women’s speech, sex discrimination through language, and asymmetrical power relations, and later moved the focus on to discourse and gender, influenced by anthropological linguist John Gumperz and sociologist Erving Goffman (Kendall & Tannen, 2015). Tanner takes a neutral viewpoint on understanding the relationship between gender and language. She argues that male-female differences in talking are neither caused by women’s inferior social status nor by male dominance. But most recent, and in the field of CDA, scholars tend to combine gender discrimination with current events. For example, Froschauer (2014) looks into South African women ministers’ experiences of gender discrimination in Lutheran Church. Western studies also have a more loosen political context and studies can be produced for other less major social groups like what Clarkson (2008) concluded, the limitations of the discourse of norms on gay visibility and degrees of transgression.

.............................

2.2 Gender Issues in Universities

As for researches concerning education or pedagogical discourse, in the review Rogers et al., (2005) published, only 46 studies are gathered. It is a review of critical discourse analysis (CDA) in education, examining the scholarship from 1983 to 2003, and years later, Rogers et al. (2016) did another review from the period of 2004 to 2012, in which the number of published articles raised up to 257. The latter review believes that the publication of Gee’s (1990) Social Linguistics and Literacies brought critically oriented discourse analysis into education research, and one of the earliest comprehensive essays devoted to CDA in education was written by Luke (1995), who issued a strong call for the importance of CDA in the study of educational practice, “A critical sociological approach to discourse is not a designer option for researchers but an absolute necessity for the study of education in postmodern conditions”. By the late 1990s, a handful of empirical studies in education were published that used the version of CDA associated with Fairclough and followers (see Rogers et al., 2005).

In the following years till now, the study trend abroad is similar to the trend at home, power and education prefer to appear in pair and the marketing of education are all popular subjects. Quite a lot of regulations in pedagogic discourse were analyzed, like Chouliaraki (1998) sought into individualized teacher-pupil talk, Mantie (2013) did a comparison of ‘popular music’ pedagogy in discourse.

However, most researchers put their focus on the discourse happening on class or on textbooks, the talk between students and teachers or how the schools marketing themselves. More silent public propaganda like banners, notes or signs haven’t seemed to reach the sight of scholars. Even though few studies have combined gender and education into one subject. Bergvall&Remlinger (1996) discussed about the role of CDA in the reproduction, resistance and gender in educational discourse, Karlson &Simonsson (2011) asked a question of gender-sensitive pedagogy as discourses in pedagogical guidelines, just to list a few.

.............................

Chapter Three Theoretical Framework.......................19

3.1 Introduction and Methodologies of CDA......................19

3.2 Fairclough’s Three-Dimensional Framework.......................20

Chapter Four A Critical Discourse Analysis of “Girls’ Day” Banners.................30

4.1 At the Description Level...................30

4.1.1 Transitivity...................30

4.1.2 Mood and Modality...............34

Chapter Five Conclusion..................59

5.1 Major Findings....................59

5.2 Innovation of the Study..........................63

Chapter Four A Critical Discourse Analysis of “Girls’ Day” Banners

4.1 At the Description Level

Halliday (1994) developed a theory of the fundamental functions of language, in which he analysed lexicogrammar into three broad metafunctions: ideational, interpersonal and textual. Each of the three metafunctions is about a different aspect of the world, and is concerned with a different mode of meaning of clauses. The ideational metafunction relates to the context of culture, the interpersonal metafunction relates to the context of situation, and the textual metafunction relates to the verbal context.

In this part of the thesis we will only adopt two aspects of his SFG tools, transitivity in ideational analysis and mood/modality in interpersonal analysis. As for textual analysis as most banners contain only one or two clauses and banners are not direcly related to one another, this thesis will not analyze much at the textual level, including cohesion/coherence and theme/rheme analysis.

........................

Chapter Five Conclusion

5.1 Major Findings

reference(omitted)